The Sources of Resilience

Findings from the largest global study of resilience and engagement from the ADP Research Institute.

Topics

We’re all suffering through difficult times that we did not anticipate and challenges that we were not prepared for. In the face of all that’s going on in the world, how do we survive? How do we push through the muck of current events and continue showing up for the people who need us most?

The answer to many of these questions lies in our capacity for resilience: the ability to bend in the face of a challenge and then bounce back. It is a reactive human condition that enables you to keep moving through life. Many of us live under the assumption that a healthy life is one in which we’re successfully balancing work, parenting, chores, hobbies, and relationships. But balance is a poor metaphor for health. Life is about motion. Life is movement. Everything healthy in nature is in motion. Thus, resilience describes our ability to continue moving, despite whatever life throws in our path. The question for us, of course, is what causes us to be able to bounce back and keep moving, what ingredients in our lives give us this strength, and how do we access them?

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Some aspects of resilience are trait-based; that is, some people will naturally have more resilience than others. (You only need to have two children to know the truth of this.) In this sense, resilience is like happiness: It appears that each of us has our own set point. If you have a high happiness set point, your happiness may wane and dip on bad days, but you will generally be happier than someone with a lower set point. Similarly, each person has his or her own resilience set point. If yours is relatively low, you will have a harder time bouncing back from challenges than, say, Aron Ralston, who got trapped while hiking in Utah and famously amputated his own arm to free himself.

How can you create for yourself — and for those you love and lead — a greater capacity for resilience, regardless of your initial set point? To answer this question, my team at the ADP Research Institute conducted three separate studies.

The first study experimented with many different sets of statements and asked respondents to rate how strongly they agreed or disagreed with each one. This helped us determine which statements had the strongest relationship to resilience-like outcomes such as increased engagement, reduced voluntary turnover, and fewer accidents on the job. From this study, we identified 10 statements that proved to be the most reliable for measuring resilience.

Second, we did a confirmatory analysis with a different sample of respondents to understand how these questions worked together and to validate the model we created from the first survey. Finally, we deployed our survey instrument to 26,000 people around the world to understand both the different levels and patterns of resilience in different countries. You can find the full results from the Workplace Resilience Study on the ADP Research Institute’s website.

In this article, we share the 10 most powerful resilience statements, what these questions reveal about the sources of resilience, and what can be done to create more of it.

The 10 Resilience Statements

Ten statements survived this rigorous analysis. Of course, we’re not suggesting that these are the only statements that measure resilience. But we do know that these statements, worded in precisely this way, prove reliable in measuring thoughts and feelings associated with resilience, and that as a group they demonstrate acceptable levels of content and construct validity. More research will need to be undertaken to establish their predictive validity.

Right off the bat, it’s clear that these statements all share two characteristics. First, each one contains only a single thought; survey statements containing multiple thoughts confuse respondents and generate “noisy” data. Second, these statements ask respondents to rate only their own feelings and experiences rather than somebody else’s attributes or qualities. This is because we humans are hopelessly unreliable raters of other people, capable of reporting only on our own subjective experiences.

At a deeper level, though, these statements pinpoint three sources of resilience. Statements 1 through 4 address employees’ own actions and mindsets, statements 5 through 7 address the actions of their team leader, and statements 8 through 10 address the actions of their organization’s senior leaders. It is this ecosystem of your own feelings, combined with how your team leader and your senior leaders behave, that creates your overall sense of resilience.

The statements also lead us to specific prescriptions for what senior leaders, team leaders, and individuals can do to increase their own and their organization’s levels of resilience, which we’ll explore from senior leadership down to individual contributors.

Senior Leaders

If you are a senior leader looking to build resilience in your teams (and teams of teams) within your organization, you’ll want to focus on two things: vivid foresight, as in statement 8, and visible follow-through, as in statements 9 and 10.

Vivid foresight. We — your employees — don’t expect senior leaders to predict the future, but we do need you to show us that you’re able to look around the corner and see a few things that you’re certain of. Situations and circumstances change, yet some things we can be sure of nonetheless. So, please, dear senior leaders, rally us around those certainties. Tell us who we will still be serving once we round that corner. Remind us what our competitive advantages will be in the near-term future. Reanchor the values that will hold true no matter what. The more vividly you can rally these certainties — in the form of stories you tell us, or heroes you point to, or examples from your own life — the more resilient we will be.

Visible follow-through. We don’t need grand pronouncements from you. We’re aware that during extraordinary times such as these, you can’t possibly know whether you’ll be able to deliver on these grand promises. Instead, find a few things you can absolutely commit to doing — what the organization will do for its customers in the near term, or what new piece of tech will be provided for a particular group of employees — and do them. Then shine a spotlight on them and show us how your commitments led to action. These small commitments may relate to only a small subset of employees rather than all employees, but it doesn’t matter who’s on the receiving end of these commitments of yours. What does matter is that we see you frequently making small commitments and then delivering on them. Do this again and again, and over time our trust in you will grow, and so will our sense of resilience — a little every day and a lot over time.

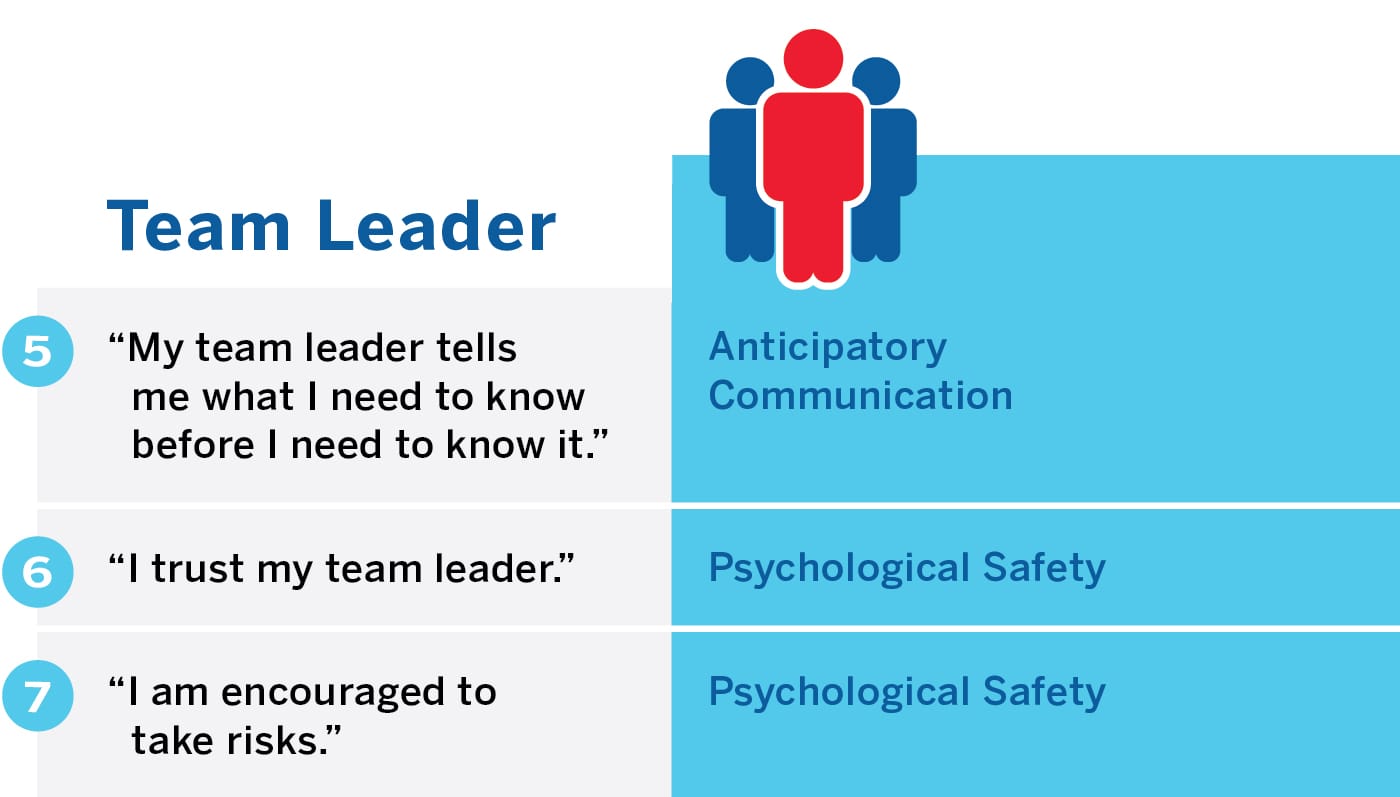

Team Leader

As a team leader, what exactly can you do to build resilience on your team? The three specifics we found can be distilled into two needs: anticipatory communication (statement 5) and psychological safety (statements 6 and 7).

Anticipatory communication. A significant body of research reveals that the single most powerful ritual shared by the most effective team leaders is a short weekly check-in with each person on the team. This check-in is a one-on-one conversation during which the team leader asks two simple questions: “What are your priorities this coming week?” and “How can I help?” No matter what their industry or level, those teams whose leaders discipline themselves to stick to this weekly check-in routine display significantly higher levels of performance and engagement and lower levels of voluntary turnover.

These weekly check-ins help each team member stay focused on the right priorities, which clearly drives engagement, but they also are an excellent way for a team leader to build resilience in the team. In each brief check-in, the conversation will naturally surface some details about the week to come. The two of you, while discussing priorities, can identify plans or processes that might need to change, gather the resources needed to get work done, and anticipate challenges that impact plans. In so doing, you will inevitably find yourself sharing things that the team member needs to know — before they even know they need to know it. And thus their resilience will grow.

Frequency of short interactions is the best response to times of dynamic change. These frequent interactions ensure that the two of you — team leader and team member — are engaging with, talking about, and making decisions in response to the real world as it actually is now, no matter how quickly it might be changing.

Psychological safety. At the start of this research, a link between risk and resilience was by no means inevitable or expected. But in statement 7, “I am encouraged to take risks,” you’ll see that one’s willingness to accept and even encourage risk-taking is a significant factor in how resilient one can feel. During difficult times, we all have to come up with new ways of getting work done. With a team leader who gives us the freedom to try new methods of collaborating, of working, of making things happen — when we feel that psychological safety — we feel more resilient.

To grow resilience on your team, be sure to emphasize that you fully expect team members to come up with new ways of doing things. Underscore that although some of these approaches will be more successful than others, you will always support people’s efforts to innovate and reinvent.

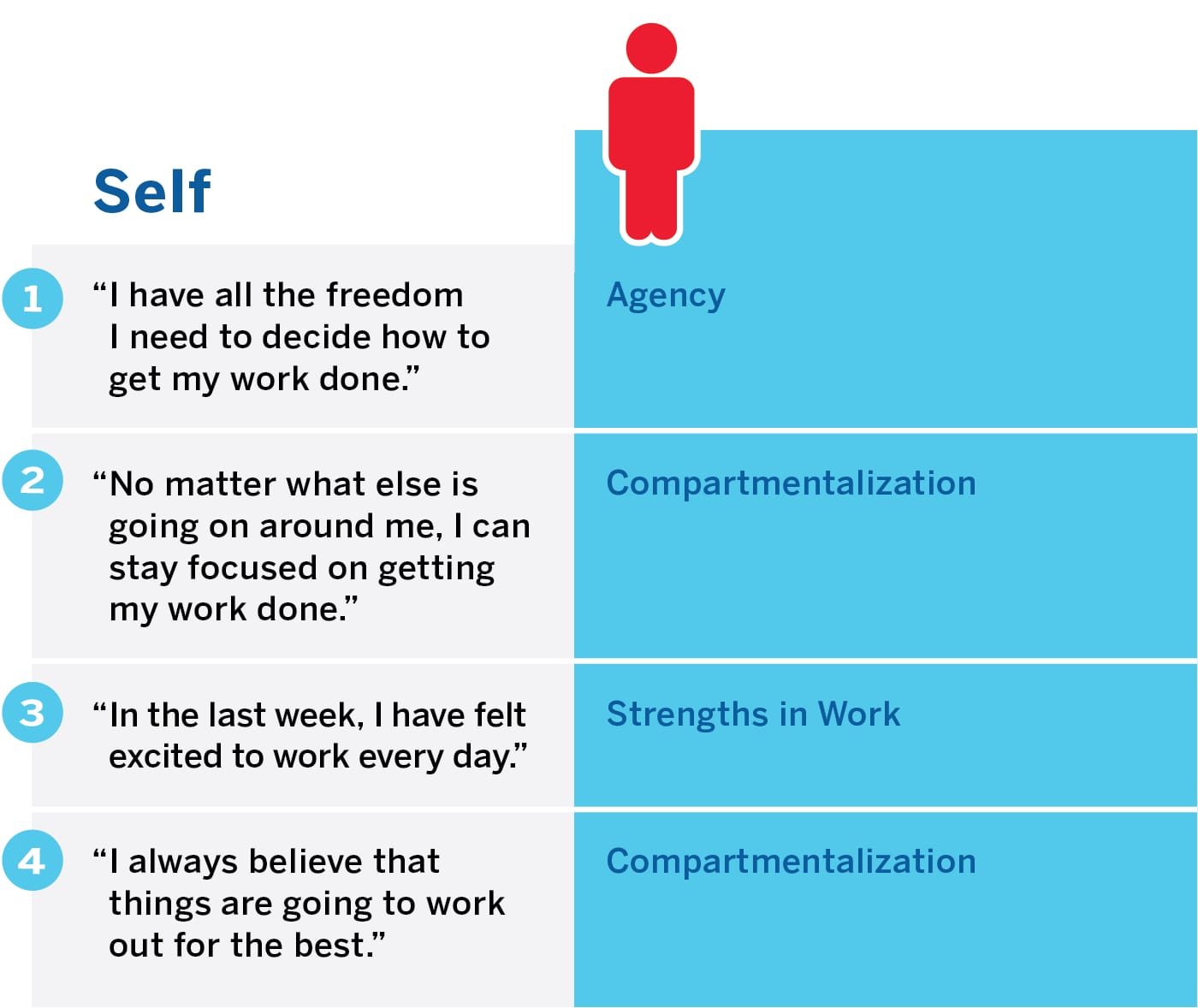

Self

Lastly, what can you do to ensure that you, yourself, are as resilient as possible?

Agency. Statement 1, “I have all the freedom I need to decide how to get my work done,” includes a clear sentiment of agency. This pandemic has emphasized that we are more responsible than ever for making our own choices. We are all tasked with figuring out how to get work done amid this stress and strain — not to mention the many distracting implications of working from home. But the more choices you have about what work to get done and when to do it, the more resilient you will feel.

For example, having a stress and recovery pattern — often a ritual that defines the end of the workday — is essential to feeling resilient, but without a physical separation between home and the workplace, many of us have forsaken our stress-recovery patterns. If you are no longer going into an office to do your work, the natural break of home versus work no longer exists and is replaced instead with one long blur of work-family-home activity.

Although the blurred line between home and work can add layers of stress upon both domains, it can also free us to make our own choices about when to work. That choice is our agency. When we have that choice around our own stress-recovery pattern, we become more resilient. To build more resilience, then, become conscious of which decisions are under your control and determine the choices you can make. For many of us, the pandemic has shattered our rituals of stress and recovery — but this new reality also means that we have more choices about when, where, and how we do our work. We may not be able to share a morning coffee with coworkers or chat with our kid’s teacher at school drop-off, but we can, and we must, create new rituals that fit us during this time. We can walk around our neighborhood during lunchtime each day, start reading The Lord of the Rings out loud every night with our 14-year-old son, or learn to roller-skate at the local park.

Compartmentalization. The next skill you can build to increase your resilience lies with statements 2 and 4: “No matter what else is going on around me, I can stay focused on getting my work done” and “I always believe that things are going to work out for the best.” Those statements reflect how well you are able to compartmentalize.

Compartmentalization is an important cognitive discipline to maintain the sense that things will work out for the best, especially when many things in your life are not going well. The most resilient people seem to realize that life encompasses a number of different lanes, as in a swimming pool. Each swim lane — family, work, physical well-being — is important. Resilient people recognize that although they may be struggling in one swim lane, they’re still coasting along in others. To build resilience, when one thing is going poorly in a single aspect of your life, don’t let it undermine everything else that you have going for you.

Strengths in work. In statement 3, “In the last week, I have felt excited to work every day,” it’s clear that resilience is in part related to your ability to derive strength from your job. Although it may seem counterintuitive, you can actually gain more resilience through work than in spite of it. We each draw strength, love, and joy from very different activities, contexts, and people — one person might get a kick out of closing a sale, while another shies away from asking for the close; one person might love finding patterns in data, while another might be bored by data, lighting up only when it’s time to take action; one person gets a jolt from checking tasks off a list, while another shines only when responding to the emotional state of each teammate. Each of us draws strength from different activities. The most resilient people are able to look at the work that they do and determine which parts of it bring them strength.

Do you know which parts of your job bring you strength? Now would be an excellent time to dig in and learn. When you know which parts of your work strengthen you, pay attention to them. Focus on the activities and situations that bring you joy, because you’re going to need those reservoirs of strengths. Your job in life is to understand and increase the activities that bring you joy in work. You don’t need to fill your day with them — research by the Mayo Clinic suggests that spending merely 20% of your day on activities that you love can have strongly positive effects on your resilience — but you do need to identify which activities you enjoy and cultivate them as a part of your personal resilience ecosystem.1 Stay focused on the activities that strengthen you, and consciously draw their energy into your working life. Getting distracted is the enemy of resilience.

In these times, we could all use a bit (or a lot) more resilience. It is my sincerest hope that this research will help you to understand what causes and impacts it, what your team leader and senior leaders are accountable for, and most important, what you can do to cultivate resilience within yourself.

References

1. K.D. Olson, “Physician Burnout — A Leading Indicator of Health System Performance?” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 92, no. 11 (November 2017): 1608-1611.

Comments (2)

Chris Prusiecki

Chris Prusiecki