Should the CEO Be the Chairman?

The practice of separating the two top jobs is common in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, but it is not necessarily an improvement over the U.S. model of combining the two positions.

As a result of recent corporate scandals, reformers and investors have increasingly called for U.S. companies to separate the chairman and CEO jobs — a model of corporate governance that is prevalent in the United Kingdom (as well as in most European countries, not to mention Australia, Canada and New Zealand). At first glance, splitting the two positions makes sense. After all, the same person acting as chairman and CEO looks suspiciously like the proverbial fox guarding the chicken coop. But most large U.S. public corporations continue to combine the two top jobs, generally splitting them only as a temporary measure (for example, to facilitate a CEO’s upcoming retirement).1 All of which raises the following question: Does separating the chairman and CEO jobs necessarily result in more effective leadership and better governance?

To answer that, we examined both British and U.S. boards, interviewing more than 50 directors in major public companies in the two countries.2 We found that the U.K. model is not the panacea that its advocates suggest. This is not to say that the emerging consensus that U.S. boards need independent leadership3 is wrong. In fact, it’s dead-on right. But achieving such leadership by splitting the two positions has its own characteristic problems, and this arrangement is not necessarily a clear improvement over the U.S. model.4

The British Model

Of the 100 largest British companies, all but a handful separate the CEO and chair positions.5 Of those that do, about three-quarters have chairs who are nonexecutive or part-time. Most nonexecutive chairs are former CEOs, usually from a different company. They may devote as many as 100 days per year to a company. In addition to leading the board, they generally chair the nominations committee and may also serve on (but typically do not chair) the compensation and/or audit committees. These nonexecutive chairmen also help determine the board’s agenda and the information the directors need. The CEOs’ interactions with boards between formal meetings are largely through their chairmen, who see themselves both as bridges to the nonexecutive directors6 and as principal representatives of the shareholders, to whom they are ultimately accountable.

The simple conventional wisdom in the United Kingdom is that the chairman runs the board while the CEO runs the company. The reality, though, is more complicated. Nonexecutive chairmen may assume a range of activities, from a monitoring role to a much more engaged one, in which they might even have executive responsibilities. They will often, for example, take an active role in the formulation of strategy. As one chairman in the United Kingdom notes, “The wise CEO would make sure that long before it gets to the board, strategy … will be discussed fully with his chairman … , and disagreements will be talked out.”

British chairmen also often share responsibility with the CEO for being the voice of the company. They preside at the annual shareholder meeting, at which they typically have the floor for far longer than the CEO. Their “letter to shareholders” precedes that of the CEO in the annual report. It’s not unusual for a chairman to meet with major shareholders to sound them out about issues such as CEO succession and compensation. And British institutional shareholders usually ask to speak with the chairman when they are dissatisfied with management and are attempting to press for change.

Strengths and Weaknesses

A key strength of the British model is that a separate chairman empowers the board vis-à-vis the CEO. The board has a clear leader for whom its functioning is a top priority. According to one director familiar with boardroom realities on both sides of the Atlantic, the CEO/chairman in the United States is typically more engaged in the chief executive role, “trying to get his agenda accomplished,” whereas the nonexecutive chairman in the United Kingdom is “much more interested in ensuring there’s an open debate.” In general, British chairmen pay much attention to the functioning of the board — its agenda, the adequacy of the information provided, the quality of debate — because that’s their primary raison d’être. This role enhances the board’s oversight capabilities. Furthermore, when a separate chairman is leading the board, the board does not need to turn against its own leader to remove an underperforming CEO.

Another strength of the British model is that the CEO can focus on running the company without having to worry about leading the board. Furthermore, chairmen who are able to help represent the company externally can lighten the CEO’s load substantially. Indeed, a high-status chairman can have tremendous value in placating unhappy shareholders and representing the firm to governmental bodies, trade associations, employees and suppliers as well as assuming other responsibilities. Even the British chairman’s more executive-like activities (such as playing an active role in strategy and even occasionally helping negotiate an acquisition) can be very beneficial. Although strategy formulation is a core executive responsibility — clearly in the domain of the CEO — many British chairmen can and do offer valuable input in the strategy discussion before a proposal is brought to the full board. Finally, the chairman can be a mentor, adviser and confidant to the CEO, providing someone to talk with more openly than might be possible with subordinates.

Because the mix of the chairman’s activities is complicated, however, the lines of responsibility among the chairman, CEO and board are not always clear. Not surprisingly, then, the British chair and chief executive can sometimes be mired in sensitive territorial issues and even power struggles, making the split structure problematic. As one chairman puts it, “There’s a great danger of confusing people about the leadership of the company.”

The difficulties often start with the fact that chairmen wield considerable power stemming from several sources. The first is, quite simply, physical proximity. Chairmen typically have their offices at company headquarters, and they may be there two or three days a week, perhaps in addition to daily telephone and e-mail interactions with the CEO. Another factor is that the average age of the chairman of a Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 company is 62 years,7 almost a decade older than the typical CEO. And chairmen enjoy a higher societal status in the United Kingdom, where such distinctions are especially important. As one British executive remarked, “The invitation to the Lord Mayor’s banquet … is more likely to go to the chairman than the CEO.” Lastly, perhaps the most obvious source of the chairman’s power is his influence with other board members, especially the nonexecutive directors. Although most British CEOs are supposed to report to the full board, chairmen come to personify the board’s authority. Moreover, CEOs recognize that chairmen will ultimately have much to say about their performance — and about whether they keep their jobs.

For the split structure to work, the chairman must exercise some degree of self-restraint, which can be difficult for someone with so much power, particularly when he has strong views, a persistent taste for the limelight and recent experience as a successful CEO (especially if he has headed the same firm that he is currently the chairman of, which is the case in about a quarter of the 100 largest U.K. firms). As one chairman admits, “You find yourself having to hold back and to bite your tongue.” The big temptation, notes another chairman, “is to use one’s power at the board and … run a sort of campaign against the chief executive … to try and make him more like you.”

There is another downside to chairmen who overstep their bounds: Not only do they encroach on the CEO’s territory, but they also decrease their independence from management. This situation can be problematic, because director independence is at the heart of effective governance. A widespread view is that governance and management are separate activities — the board needs to keep its distance from management so that it can be an independent monitor — and that the chairman ought only to lead the board.

Sometimes, though, a chairman needs to step in. One chairman asserts that in normal times, the chief executive is leader of the firm, but at other times — for example, during a company crisis — the two individuals share the leadership. The issue of who is leading the company gets murkier when a CEO is failing to get the job done. As one chairman puts it, “At the end of the day, the chairman has the ultimate responsibility for the company. And he can’t escape the responsibility for disciplining the CEO.” But that, in a nutshell, is the problem: When leadership varies according to circumstances and when people are unclear regarding the division of responsibilities, some degree of confusion is likely to result.

The U.S. Model

The U.S. model, which can be viewed as a concrete expression of the U.S. cultural belief in a single strong leader, precludes any confusion — inside or outside the firm — as to who is really in charge. According to the model’s proponents, CEOs need unambiguous power to lead, especially when pushing changes through organizational resistance. As a former CEO/chairman of a U.S. company explains, “One absolute boss is not a comfortable way to live, but it’s a very effective way to do things.” Moreover, given the dominant U.S. practice of combining the two jobs, a board that separates them might be signaling low confidence in its CEO, damaging that individual’s credibility and effectiveness.

Combining the two top positions also has governance advantages. According to a director with extensive British and U.S. experience, “It’s pretty clear in the big American corporations … where the buck stops.” In contrast, at U.K. firms, the line of accountability isn’t always well defined, which leaves boards in a quandary when things go wrong (should the chairman, the CEO or both be fired?).

The Future of U.S. Boards

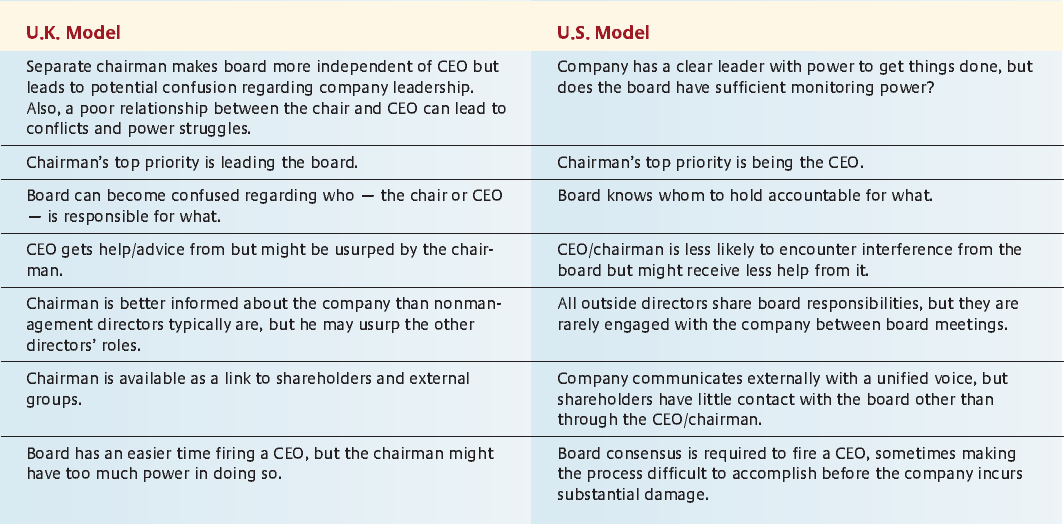

In summary, neither of the two models is a perfect solution to the challenges of good governance and effective executive leadership. Each has its pros and cons (see “U.K. Versus U.S Models of Board Leadership.”), and no compelling argument exists for splitting the chairman and CEO jobs, particularly in light of the fact that U.S. senior executives strongly believe that the two positions should remain combined.

This, however, does not mean that U.S. boards should never split the jobs. But any board that does so should design the chairman and CEO roles carefully, taking into account the lessons of the British experience. What’s at stake — the effective governance and leadership of the company — is far too important to simply leave the two individuals to sort matters out on their own without any formal guidelines.

U.S. boards that retain the combined model also need to keep some lessons in mind. Various forces, including the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 20028 and the new stock exchange listing requirements,9 are putting increased power in the hands of independent directors. Because these individuals need a leader who is not also the CEO/chairman, many boards have designated a “lead” or “presiding” director from among the independent board members. This role is not the same as chairman. Rather, it is a position with essential but deliberately limited responsibilities. The most significant of these responsibilities is to convene and lead meetings attended only by the independent directors so that, for example, they can openly discuss the CEO/chairman’s performance and compensation. Beyond that, the duties of the lead director should be limited, perhaps to reviewing the agenda with the chairman in preparation for board meetings and to facilitating the work of board committees.

Restricting the scope of the lead or presiding director’s job recognizes two key realities. First, the chairman (and CEO) is the board’s leader. Second, all the directors are jointly responsible for the governance of the company. Allowing the lead director’s job to expand contradicts these two principles and is likely to result in boardroom conflicts. After all, a lead director who encroaches on the CEO/chairman’s territory would be like the British chairman who oversteps his CEO, causing the same kinds of problems.

VARIOUS SCANDALS HAVE recently shaken people out of their complacency regarding corporate governance, but a knee-jerk reaction to adopt the British model of company leadership without understanding its complexities is hardly the answer. For most large U.S. companies, adding a competent lead or presiding director will likely strike the right balance between effective governance and leadership. But for those boards that choose to split the chairman and CEO jobs, the lessons from the United Kingdom should not be ignored.

References

1. According to a March 2004 study, 75% of the CEOs of S&P 500 companies are also the board’s chairman, down slightly from 79% as of February 2003. Of the S&P 500 companies that did not combine the two jobs in March 2004, at 65 of those organizations the chairman was the company’s former CEO. See “Governance Research From the Corporate Library — Split CEO/Chairman Roles — March, 2004,” www.thecorporatelibrary.com/Governance-Research/spotlight-topics/spotlight/boardsanddirectors/SplitChairs2004.html.

2. These directors included 18 chairmen (holding a total of 24 chair positions among them) and five CEOs of the 100 largest British companies, as well as 17 former or current Fortune 500 CEO/chairmen.

3. See M. Lipton and J. Lorsch, “A Modest Proposal for Improved Corporate Governance,” The Business Lawyer 48, no. 1 (1992): 59–77.

4. This article draws extensively from A. Zelleke, “Freedom and Constraint: The Design of Governance and Leadership Structures in British and American Firms” (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2003).

5. D. Higgs, “Review of the Role and Effectiveness of Non-Executive Directors” (London: Department of Trade and Industry, 2003).

6. The British prefer the termnonexecutive director to refer to board members who are not part of management (calledoutside directors in the United States). British nonexecutive directors make up less than 60% of the board of the typical Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) 100 company (that is, the top 100 British companies ranked by market capitalization); the other directors are high-ranking executives of the company. In contrast, fully 80% of Fortune 100 board members are outside directors.

7. Higgs, “Review of the Role and Effectiveness of Non-Executive Directors.”

8. Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Public Law 107-204, 107th Congress, enacted July 30, 2002, http://news.findlaw.com/hdocs/docs/gwbush/sarbanesoxley072302.pdf.

9. See New York Stock Exchange, “Final NYSE Corporate Governance Rules,” approved by the Securities and Exchange Commission on Nov. 4, 2003, available at http://www.nyse.com/pdfs/finalcorpgovrules.pdf; and NASDAQ, “NASDAQ Corporate Governance Summary of Rules Changes,” approved by the SEC on Nov. 4, 2003, www.nasdaq.com/about/CorpGovSummary.pdf.