Leveraging the Power of Intangible Assets

Despite its potential, few managers have begun even to scratch the surface of information about intangibles and the opportunity it offers.

Topics

Many managers have been looking forward to when they can track information about their intangible assets — for example, the value of their brands or the quality of their human talent — as easily as they monitor cash flow and market share.1 Inspired by the works of strategy theorists such as Robert Kaplan and David Norton, they have anticipated a day when it would be possible to keep track of customer sentiments, innovation and employee skills with real-time data, just as they manage profit and loss.2 Whether managers are aware of it or not, that day is almost here. Thanks to advances in information technology, managers of consumer-oriented businesses have the ability to track not only the percentage of satisfied customers but also the reasons why people are satisfied or dissatisfied. Companies in other industries can use IT and industry data for their own purposes — for instance, to follow opportunities for patent licensing or acquisitions. Despite the potential, most managers have been slow to respond. Few have begun even to scratch the surface in seizing the opportunities that information about intangible assets offers.

Different companies, of course, have different types of intangible assets. The most common include licenses, franchises, patents, trademarks, brands, knowhow, market competences and human resources. For many companies, the mix of intangibles represents a large percentage of the total corporate value, as measured by stock market valuation, investment level or perceived importance.3 A 2003 study by Accenture and the Economist Intelligence Unit found that 94% of the global executives surveyed saw comprehensive management of intangibles and/or intellectual capital as important, and half considered it one of the top three issues facing their organizations.4 But management awareness about how to take advantage of this value remains surprisingly low.

Until recently, there were good reasons why managers paid scant attention to information about intangibles. Companies had no regulatory obligation to disclose information about intangible assets to shareholders the way they had to disclose, say, executive compensation or pending litigation. In addition, most managers had limited experience dealing with intangibles. Those who were familiar with intangibles mostly relied on intuition to choose appropriate valuation methods for mergers and acquisitions as well as simple surveys to gauge employee morale. In general, managers were reluctant to introduce new methodologies without a clear understanding of the return on investment. Lately, however, factors including globalization and shorter innovation cycles have been changing the overall context. On a regulatory level, the European Union is introducing standards for reporting on intangibles. More broadly, some managers are beginning to see how managing intangibles well can lead to advantages in the marketplace in terms of better customer service, faster product improvement cycles or public/media perceptions. Although information about many intangibles (such as reasons for customer dissatisfaction) is not as available as information about tangibles (the book value of a building or profit per customer or account receivables, for instance), it is getting easier to access all the time. Indeed, the proliferation of data and advances in IT — specifically, in areas such as text mining, data mining and information integration5 — have made it increasingly possible for companies to define, capture and monitor information critical to managing the business.

Consider the case of an auto manufacturer. In the past, if a problem was not big enough to draw the attention of government regulators, the issue might not surface for several months. Aside from poring over copies of individual service records of dealers, monitoring customer help lines or reading through thousands of newspapers, finding out about a possible defect affecting a small number of products was difficult. Information integration has changed all that. Today, auto company managers can pull in information from hundreds of different sources; mine the text and data for details and patterns; and spot problems as they arise. Such capabilities have created opportunities for companies to revamp products more quickly. These capabilities have also opened up new frontiers for building customer loyalty, some of which are being actively explored by companies in other industries.

Choosing Intangibles That Matter

How do managers go about selecting the right kind of information about the intangible assets they want to track? Out of all the information they can tap, how do they home in on the most meaningful data? Contrary to what many managers may think, it’s possible to find useful information about most types of intangibles, although some kinds will be easier to access and monitor than others.6

One’s choice of information needs to be aligned closely to the nature of the business and management’s objectives. Although the technical infrastructure for accessing a variety of different types of content is readily available (and companies are becoming more competent at searching data repositories of both text and structured data), managers still need to be clear about precisely for what they are looking.

In light of what they want to accomplish, managers need to ask some basic questions about what information they need, and where that information resides. Some information is easier to define and access than others. For example, companies looking to track how customers perceive their products can learn about that in several ways. At one end of the solution spectrum, they can subscribe to services that collect product reviews or solicit direct feedback from customers. At the other end, they can use technology to monitor and analyze media coverage about their products and those of their competitors, and study warranty reports and call-center data. Most solutions fall somewhere in the middle: Companies do their own analysis of call-center data. Each of these approaches uses a different level of resources: people, data and technology.

Can the Information Extraction Be Automated?

Once managers identify the kind of information they want to track, they need to understand the range of available mechanisms for extracting it. Extracting information the traditional way, by relying on human analysts, can be a tedious process that involves sifting through mountains of data (for example, notes taken by customer service representatives). However, depending on the context, human efforts can often be augmented with technology, enabling continuous and cost-effective business process support.

The accuracy of text-mining modules varies greatly, depending on the nature of the questions and the text and data quality. Classifying incoming e-mail by a computer, for example, tends to be more accurate than by a human analyst; in cases involving more subjective or complex information (such as customer sentiment or participants’ feedback at events), automated systems are nowhere near as accurate. If there is an abundance of data, however, the performance of automated solutions tends to improve over time.

In many applications, such as customer relationship management, the essential goal is to develop a clear understanding of what people are saying. (Do they like the product or don’t they? If so, why?) To answer these questions, an automated system needs to perform well only on a statistically meaningful sampling of responses. (It might alert managers to an offer by a competitor that is motivating a particular segment of customers to switch products.) Even when the system does not deliver a complete set of information about the attitudes of all customers, it is almost always cost-effective. It will give managers insight into a problem before it becomes a major headache.

Successful first-time deployment of new analysis tools usually depends on three criteria: access to raw data; confidence that the particular type of advanced technology works, based on the experiences of others; and minimal disruption of business processes.

In most cases, raw data are widely available in relational databases and online textual documents. Organized access to distributed data can be achieved through information integration, a relatively mature technology provided by several large vendors. The advanced capabilities of text- and data-mining technology are quickly becoming mainstream. Indeed, for almost any type of enterprise information, we can find examples of both vendors delivering extraction capabilities and companies using them. Once the information has been extracted, it is but a small step to include it in regular reporting applications. In almost every business environment, opportunities are waiting to be tapped.

The fact that opportunities exist does not suggest that technology should always be used in place of human judgment. On the contrary, people can make many decisions more effectively, especially ones made in unique cases or situations requiring common-sense knowledge. Routine decisions, however, often can be successfully automated. More often than not, computers will provide good enough answers to well-defined questions at a fraction of the cost.

Building Comprehensive Solutions to Leverage Intangibles

To the extent that companies use automatically extracted information about intangibles at all, they are mostly using it in fairly narrow ways. A typical example can be found in call centers, where companies analyze data about customer preferences to improve the profitability of certain customer segments. But managers looking to create more successful businesses have to begin leveraging information about intangibles more robustly — across multiple areas of the business at once. Among other things, this can lead to enhanced profits and improved capabilities for innovation.

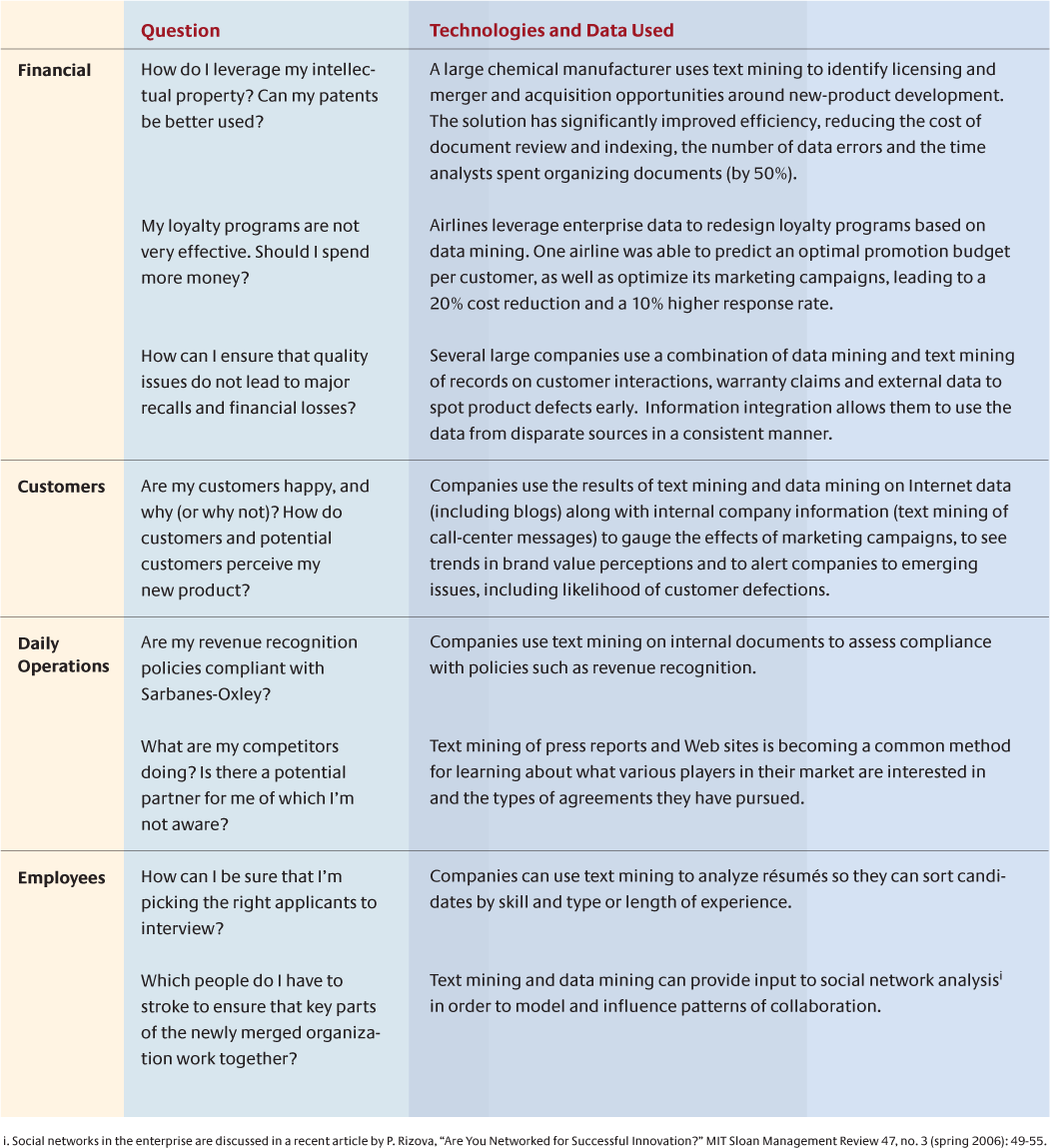

Deciding which information is most vital to track depends on the circumstances of the business. Although in an ideal world managers might want to have a few dozen intangibles in view, they will have to prioritize — perhaps monitoring fewer than a dozen on a steady basis. Managers need to begin with basic questions: What do we want to understand? What information will lead to an answer? And how well will the information and technology answer the questions? (See “Monitoring Information About Intangibles.”)

Consider the case of a company that wants to improve its level of customer retention. Managers can initiate the process by asking questions about customer satisfaction. At its simplest level, they will want information showing the percentage of customers who are satisfied with the company’s products or services. In addition, they may want to see detailed breakdowns of the reasons for satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Depending on what data are available, they may or may not be able to get information about customer attitudes. At a minimum, they will see which customer segments are happiest and which are unhappiest, and if they want to go further they can initiate other inquiries. If they do have the right customer data, they can apply technology to extract reasons for positive or negative customer attitudes and then recommend changes to the products or services. Thanks to these capabilities, managers can monitor the data on an ongoing basis, allowing them to improve products, shorten product life cycles and generate increased levels of customer loyalty.

What’s more, the improvements can be part of an ongoing, iterative process, where the management insights lead to new questions and insights that affect how the company does business. Whatever changes companies make will lead to a new set of information needs.

Regardless of the particular areas managers are interested in, the overall approach should be essentially the same. The initial role of management is to frame the questions that need to be answered. The role of IT professionals is to determine what types of data exist and the range of possibilities for accessing and analyzing them. For example, does the company have the necessary skills and infrastructure to perform the work internally, and can the work be done using off-the-shelf software? Or will it need to retain specialists and invest in new proprietary software? Ultimately, managers will need to determine whether the answers they seek are available at a reasonable cost.

In addition to the financial costs, managers need to consider the risk factors, including all the potential impacts of introducing new systems, hiring new people and deploying new technologies. Depending on the circumstances, these costs may or may not be deemed to be acceptable.

The potential for using information about intangibles has evolved to the point that it is no longer a matter of whether companies can access important data and put them to use. Rather, it is a matter of what the most comfortable entry point will be. Managers will have to reach this conclusion for themselves based on a set of factors: the nature of the questions they want to answer; the quality of the data available; the technology they need to use; and the extent to which major process changes will have an impact the organization.

IMPLEMENTING INTANGIBLES-ORIENTED REPORTING IS NOT EASY. There are the technical obstacles, not the least of which are the quality of enterprise data, the existence of data silos and fragmented responsibility for data and a shortage of employees with text- and data-mining skills. In addition, there continue to be business obstacles. Many executives believe that intangibles are too “soft” to measure and manage; others are waiting for the regulatory requirements, which are still unfolding, before they invest time and effort on information about intangibles.

Yet the opportunity is ripe for exploitation. The technologies and the necessary infrastructures exist. The data from which information can be extracted are widely available. In most cases, current reporting systems require only minor adaptation. Thus, it is quite reasonable to anticipate that companies will become increasingly focused on managing their intangibles over the next few years. Those who manage to do it sooner and better are likely to gain disproportionate competitive advantage.

References

1. The termsintangible assets orintangibles refer to any nonphysical assets that can produce economic benefits. They cover broad concepts such asintellectual capital, knowledge assets, human capital andorganizational capital as well as more specific attributes likequality of corporate governance andcustomer loyalty.

2. R.S. Kaplan and D.P. Norton, “Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004) provide a strategy and management view of intangibles. B. Lev, “Intangibles: Management, Measurement and Reporting” (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2001) discusses intangibles chiefly from an accounting perspective. A broad, more technical, discussion of intangibles is given in J. Hand and B. Lev, eds., “Intangible Assets: Values, Measures and Risk” (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), which discusses management, valuation and economic issues.

3. The editor’s introduction to two articles on intangible assets in Harvard Business Review 82 (June 2004): 108, states: “Everybody knows that in the modern corporation intangible assets are the source of greatest value.... The nonmanagement of intangible assets has measurable costs.”

4. A summary of the Accenture study, “Survey Results on Accounting for and Managing Intangible Assets,” can be found at: www.accenture.com/Global/Services/By_Subject/Shareholder_Value/R_and_I/SurveyAssets.htm.

5. I use the termstext mining anddata mining broadly to refer to any type of automated analysis of collections of text documents and data in databases. For example, text mining can include not only data extraction from text but also automated classification of content in documents.

6. See W. Zadrozny, “Text Analytics for Asset Valuation,” IBM research report RC23311, IBM Corp., Yorktown Heights, New York, 2004. I present a comprehensive list of 90 different types of intangible assets mentioned in academic research, consultant reports and during mergers and acquisitions. I also discuss the status of text- and data-mining technologies and specific cases where they have been used to monitor intangibles. In W. Zadrozny, “Making the Intangibles Visible: How Emerging Technologies Will Redefine Enterprise Dashboards,” IBM research report RC24020, IBM Corp., Yorktown Heights, New York, 2006, I describe how the monitoring of intangibles can be integrated with existing enterprise reporting applications. The research is based on published cases of enterprises using the technology to monitor their intangible assets. It presents details of an argument that monitoring opportunities exist for more than 80% of intangibles and describes cases where multiple text- and data-mining modules are used together. Both reports are available at http://domino.watson.ibm.com/library/cyberdig.nsf.