How Should Board Directors Evaluate Themselves?

Board self-evaluations are now a requirement at many companies. But what’s the most effective way for directors to assess their own performance?

Board directors are facing increasing scrutiny. In the wake of the New York Stock Exchange’s own scandal with its former CEO Richard Grasso,1 the NYSE now requires the boards of all the companies it lists to conduct periodic self-evaluations. Furthermore, both Morningstar and Standard & Poor’s2 consider board self-evaluation as one criterion in their governance ratings of corporations. The practice has even become increasingly mandated in the nonprofit world. The National Association of Independent Schools, for example, currently requires the boards of private schools to conduct self-evaluations. And board directors in the United States aren’t the only ones feeling the pressure. In Finland, for instance, the boards of all public companies must routinely assess their own performance.3 Still, the practice is far from universal. NASDAQ, for one, does not currently require board self-evaluation of its members. Nevertheless, NASDAQ companies that do undertake board self-evaluation have the opportunity to get ahead of the curve and position themselves in the vanguard of good governance.

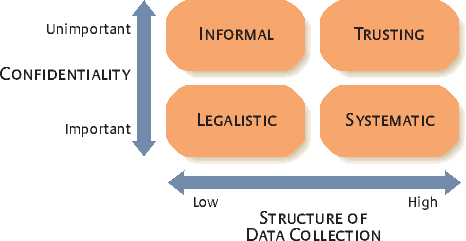

But what exactly is the best way for a board to evaluate itself? Unfortunately, board directors have generally had little guidance in this area. To investigate the different self-evaluation practices used, we studied eight boards that have engaged in self-evaluations for at least two annual cycles. We found that the companies were using a variety of practices for collecting data and for preserving the confidentiality of this information. The differences among these practices can be summarized by four distinct approaches to self-evaluation: informal, legalistic, trusting and systematic. Each of the approaches has important implications for a company’s board rating, directors and officers (D&O) insurance and various legal issues.

Why Self-Evaluations?

In a 2004 survey conducted by Korn/Ferry International, 72% of board directors indicated that their performance ought to be evaluated. Yet only 21% of the boards of public companies actually conduct such assessments. Part of the problem is that organizations often don’t know how best to implement a board self-evaluation procedure. Many simply avoid the practice because they fear alienating individual directors. Others have implemented the process only to become frustrated because it took so much time and produced so few results.

According to James Doty, a partner at Baker Botts in charge of the international law firm’s board self-evaluation program, companies need to address two core governance dilemmas when implementing any self-evaluation procedure. Specifically, Doty contends that a board needs to (1) encourage bold decision making by the CEO without becoming a passive entity that permits imprudent risks; and (2) maintain an environment of collegiality while avoiding the danger of creating harmonious but dysfunctional “group think.” Achieving both objectives is easier said than done, but a self-evaluation process that is properly designed can be a substantial aid.

Any self-evaluation practice should be designed and structured so the board can investigate the following: How are we as a board contributing to the overall effectiveness of the organization? At many companies, a self-evaluation might be the only time during the year when the board asks itself such a fundamental question. During such a meeting, the directors should focus mainly on reviewing management’s contribution to shareholder value.

When conducted properly, self-evaluations can be a powerful tool for improving the board’s performance. A 2003 study by Mercer Delta Consulting found that self-evaluation was significantly related to board effectiveness with respect to specific functions, such as the ability to balance the interests of different stakeholders. The following cases illustrate just a few of the myriad ways in which self-evaluations can bring to light certain problems that could easily undermine board performance.

Embracing Half-Baked Ideas

At a small public company, the demands of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act had moved board meetings to a focus on compliance. The board was continually asking the CEO: “Have you done this?” “When will you do that?” and “Why did you do this?” Not surprisingly, the meetings had become adversarial.

Through a structured self-evaluation, the board concluded that it had two critical roles: (1) protection of shareholder value through auditing and overseeing management performance and (2) enhancement of shareholder value through providing its collective wisdom to help management move in new strategic directions. Thanks to the evaluation process, the board realized that the demands of its first mission had taken over the requirements of the second. To correct this, the board established a “half-baked ideas” program. Whenever the CEO or other senior managers wanted to brainstorm or bring a speculative proposal to the table, they would remind the board of the new program. The board would then refrain from any knee-jerk criticism and instead focus on being receptive and supportive of management’s outside-of-the-box thinking.

Confronting the Trophy Director

The nominating committee of a nonprofit organization was flattered when the CEO of a well-known national company accepted an invitation to join the board. Having this “trophy director” gave the entire organization added cachet, but, unfortunately, the individual contributed little else. When he did attend meetings, he tended to vote for whatever the emerging consensus seemed to be. Nevertheless, everyone seemed to accept the situation, and nobody confronted the trophy director about his lack of involvement.

Then the board conducted a director self-evaluation. In response to a query that asked how well the individuals on the board seemed to understand the major trends affecting their industry, the directors all rated themselves and their fellow members highly, with one exception: the trophy director. He not only received low ratings from others but also was honest enough to rank his own performance as below par. In addition, a review of the attendance records of full board and committee meetings revealed that only the trophy director had poor attendance.

This information finally forced the board’s hand. The chairman confronted the trophy director, who freely admitted giving the board a low priority because he needed to focus on the business imperatives at his own company. So the chairman and the trophy director agreed that they should part ways. The director was grateful that he could resign quietly to spend more time with his company, and the board was happy to fill the seat with someone who would be more committed. Subsequently, the trophy director and company have remained on good terms, which might not have been the case had the situation been allowed to fester, with other board members becoming increasingly resentful toward the trophy director.

Rethinking Board Meetings

The CEO/chairman of a Fortune 500 corporation usually brought his direct reports to board meetings. This group of executives included the CFO, chief legal officer, CIO, chief marketing/sales officer, head of HR and COO. The CEO/chairman’s rationale was that he wanted to encourage the board to ask his managers specific questions about their departments. He also wanted those senior executives to gain valuable firsthand experience in understanding the board’s concerns. Who could argue against such logic?

A director self-evaluation, however, revealed a problem. As it turned out, the directors often found themselves withholding their feedback to the CEO because they feared embarrassing him in front of his subordinates. Once that issue was uncovered, it was dealt with quickly, and management attendance was limited to the CEO, CFO and chief legal officer, with the other executives invited on an as-needed basis.

The Pros and Cons

Board self-evaluation also has ancillary benefits. The practice can help enhance investors’ perceptions of a company, particularly if self-evaluation is implemented before it’s required. This is the opportunity that NASDAQ companies currently have. In fact, the more seriously a firm takes governance, the more attractive it will be as an acquisition candidate to larger corporations that are particularly concerned about minimizing any potential risks from shareholder lawsuits.

Typically, board directors are concerned about two types of personal risk. The first is financial risk (for instance, from a shareholder class-action lawsuit), which can be managed with D&O liability insurance. The second is risk to their professional reputations. A board self-evaluation can alienate directors who feel they should be above the process, especially when they want to preserve their reputations and they know their contributions have been lacking. Sometimes, a director might even resign in protest of an impending self-evaluation. But any board that loses such individuals is probably better off without them, and other directors are often more relieved than upset with those types of resignations.

This raises the key issue of board culture, which is an important factor not only in a board’s ability to attract good directors but also in its trickledown effect within the organization as a whole. That is, any dysfunctional board behavior, such as unnecessary finger pointing, tends to find its way down to middle management. A structured program for self-evaluation is one component of a system to attract and retain competent directors who are unafraid of a culture that says: “We have a responsibility to evaluate the CEO’s effectiveness as well as our own. Continuous improvement is something we expect of our management and of ourselves.” Such a positive attitude is likely to permeate throughout the organization — for instance, with managers taking employee performance evaluations more seriously.

Another benefit of board self-evaluation is that the practice can help pave the way for favorable D&O premiums. According to the American International Group Inc., the largest carrier of D&O insurance, a systematic ongoing program of board self-evaluation could become a favorable factor that underwriters take into account when establishing D&O premiums for companies in the future. This area is a new frontier for insurance companies. In the beginning, underwriters might simply be asking, “Does your board routinely conduct self-evaluations?” — a yes-or-no question. But as the insurers become more sophisticated about the practice, they are likely to start asking for additional information, with such requests as, “Describe the evaluation process that you use.”

With all the benefits, why do many boards choose not to conduct regular self-evaluations? One of the major reasons is time limitations. Over the years, the time commitment for board membership has continued to escalate. According to one survey, membership on the board of a public company typically requires 100 hours per year, and serving on the audit committee necessitates an additional 200 hours. Already pressed for time, many board members perceive the self-evaluation process as additional work that is not necessarily worth the effort.

The possibility of litigation is another factor. Board self-evaluations sometimes produce information about suboptimal behavior that might then be used in civil suits or criminal trials. To avoid that risk, some companies have considered retaining a law firm to perform the board evaluation in the hope that attorney-client confidentiality will protect the information. But Delaware courts have failed to recognize such a privilege of confidentiality for critical self-analysis by directors. At any rate, when the self-evaluation process uncovers information that indicates a serious problem, the company should alert counsel immediately and pursue the matter until it is resolved in the appropriate fashion. This risk makes it important that organizations implement explicit and clear-cut policies for the retention as well as destruction of self-evaluation records. Outside advice from legal counsel is often invaluable in writing those policies.

In addition to legal risks, investors and employees can suffer from demoralization if the board fails to act on what it has learned. The very act of conducting a board evaluation raises expectations on the part of directors, management and key constituency groups. If the evaluation uncovers problems and the board fails to respond, morale will likely sink. Because of this, boards are often better off not engaging in self-evaluation if they are unprepared to act on at least some of the concerns that are identified.

Self-Evaluation Basics

The design of any self-evaluation program requires continual consultation with the board. Obviously, the board’s buy-in is crucial to ensuring that the new system is actually adopted and used. At a minimum, the structure, feedback and follow-up of the evaluation need to be discussed.

In our study, most of the organizations had created their own proprietary evaluation forms, usually cut and pasted from other questionnaires that were available for free. In addition to their low cost, the advantage of such instruments is that they can be tailored to the needs of a particular company. But that benefit has a downside. In the event of a lawsuit or negative media coverage, critics could contend that the self-evaluation was customized specifically to avoid dealing with crucial problems. For example, if the board is populated with powerful individuals, was the process skewed to avoid antagonizing those members? This perception can become a real issue when the designer of the evaluation form is the chairman, another director or a corporate employee.

To avoid this potential problem, some companies use a nationally accepted instrument, such as the Balanced Scorecard or the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) standards for board self-evaluation. The first tool has a protocol for board self-evaluation that ties the board to the larger Balanced Scorecard framework. As a conceptual model it is elegant in that it creates a single theme from top to bottom within a company. But it is also cumbersome to administer, and it assumes that management and governance are similar. The NACD survey is based on this organization’s blue-ribbon commission on board self-evaluation. The NACD standards are accepted within the for-profit world but they can easily be applied to nonprofit organizations as well. They cover just about every evaluation contingency, regardless of industry. Their use provides a commonly accepted gold standard and, as such, they represent a good tool for risk management. On the other hand, directors who rigidly adhere to the NACD instrument could find the process so time-consuming that it generates more board anger than enlightenment.

One solution is to use the general framework of a well-accepted tool but to customize various aspects of it. Boards that do so should keep in mind that any modifications could leave them open to charges that the instrument was altered specifically to skirt having to deal with certain problems. To avoid that perception, any changes to the self-evaluation tool should be made in consultation with an outside expert.

Once the questions are approved by the board, they can be administered by means of a paper survey or online. Alternatively, an “interventionist” could interview the board members in person or over the phone, using the questions as a framework. The interventionist would then tabulate the results and meet with the board to help the directors understand the implications of the data. As mentioned earlier, having clear rules for confidentiality and data retention (as well as destruction) is critical. Obviously, people will be reluctant to answer questions honestly if they suspect their answers might somehow be used against them or the board.

The interventionist should not be a company employee because the potential conflicts are too great. Instead, the board should consider either a member of the governance committee or an outside specialist. Selecting a board member is an inexpensive solution, and directors are usually more familiar with the pertinent issues facing the board than any outsider. They are also more likely to keep confidential information from spreading to external parties. On the other hand, difficulties can arise when the board member who is acting as the interventionist is also one of the individuals responsible for a particular problem that needs to be resolved. Furthermore, investors and the media generally look more favorably toward an outside interventionist, who is perceived as having greater objectivity.

Interventionists who are board members are typically required to maintain and destroy information in a manner that is consistent with the appropriate corporate guidelines for data retention. An external interventionist, however, is able to employ policies that are more favorable to the company, as long as those policies are followed consistently. For example, the corporate guideline for a company might call for data to be maintained for seven years, but external interventionists could destroy the sensitive results from a self-evaluation much sooner, if their firm’s policy states that confidential information should be shredded within 60 days following the termination of a project.

Four Approaches

In our study of boards that have conducted self-evaluations for at least two cycles, we found two high-level variables in the protocol for the process: the structure of the data-collection methodology (low versus high) and the confidentiality of data (unimportant versus important). Those dimensions define quadrants of four different approaches to self-evaluation: (1) informal, (2) legalistic, (3) trusting and (4) systematic. (See “Four Approaches to Self-Evaluation.”)

Informal

Data gathering is often limited to the chairman saying to the board something along the lines of: “This is the time when we evaluate our own functioning. We are not going to write anything down, and there will be no details of this discussion in the meeting minutes. Now, is there anything someone wishes to discuss?” With that, the board can check off that it complied with the requirement for setting aside time for self-evaluation. Confidentiality is not an important issue because nothing will show up in the records and members have been discouraged from writing anything down. But this approach is also likely to yield the least valid information for improving the board’s effectiveness.

Today, informal approaches are generally acceptable to board-rating services and D&O underwriters. In the future, though, more sophisticated practices will likely be required. That said, many boards commence the self-evaluation process with an informal approach because it is the cheapest and least threatening to implement. As such, it can be effective as a small first step in migrating toward another approach in the future.

Legalistic

This approach is marked by low structure for data collection and tight controls over how that information is collected and later destroyed. The instruments used are often home-grown systems or tools adapted from free samples offered by law or accounting firms. If the board culture of the informal approach is,“Let’s get the self-evaluation over with,” then the corresponding sentiment for a legalistic approach is, “Let’s do what we need to while minimizing cost, time and hurt feelings.”

A legalistic approach is the minimum that should be implemented by boards under scrutiny from shareholders, the media or other parties. Organizations should also consider having a legalistic approach in place well before making a major decision — for instance, merging with another company — which could lead to controversy and shareholder lawsuits. And any corporation with director or executive compensation substantially above the norm for its particular industry might also benefit from using, at the very least, a legalistic approach to self-evaluation.

Trusting

This approach is marked by high structure for data collection using or adapting a well-known instrument such as the NACD survey. The program is viewed as a multiyear effort with the same instrument used on a consistent basis so that progress can be monitored objectively over that period. At the same time, board members are likely to harbor few worries about data confidentiality. Consequently, data are collected through an in-house procedure, and the information is secured consistent with the company’s policies for data retention. This strategy might be an expression of supreme confidence that the company’s actions are above reproach, but it also might reflect a naive understanding of the pervasiveness of litigation in U.S. society. Here, the board culture is, “Let’s do the right things in the right ways, because we have nothing to hide.”

Clearly, a trusting approach should not be used by companies that lack the appropriate policies for maintaining and destroying confidential data. Nor should it be implemented by boards that might have difficulty justifying their decisions, particularly in a court of law. But for other boards that are serious about continuous process improvement, a trusting approach helps lay a good foundation, because it establishes an atmosphere of collegiality. The trusting approach can be ideal for the boards of consortia or trade industries. It might even be effective for a service organization, such as a credit union, which is more fraternal than performance-driven. For many companies, though, a trusting approach is best deployed as a means to establish an explicit board culture of collegiality and continuous improvement so that the organization can later migrate to a systematic approach.

Systematic

This approach is marked by two characteristics: (1) a high structure of data collection using a well-known instrument and (2) substantial concern for data confidentiality. As such, the data collection is often performed by a consulting firm or other outside entity with its own policies for data destruction that are more rigorous than the client’s corporate practice. Board members are not allowed to retain their notes and only a general statement is entered into the minutes. All procedures for data collection and destruction are stated clearly and upheld with the utmost consistency, because any discrepancy in this area tends to heighten the suspicions of outside parties, including regulators and prosecutors. Instead of home-grown instruments, the board opts for well-known tools, which helps to increase the confidence of constituency groups and D&O underwriters that critical issues will not be swept under the carpet.

A homegrown instrument administered consistently over time enables longitudinal comparisons of how a board is functioning during a given period. A widely recognized instrument such as the NACD survey has that benefit as well, and it has the added advantage of allowing comparisons among boards within the same industry that use the identical instrument. The attitude here is,“Let’s take a long-term approach, because we might be good, but we can always be better.” Ideally, a systematic approach should be the goal, but it requires substantial commitment by the board as well as a concerted effort by those implementing the process. Consequently, some organizations that are embarking on a self-evaluation process might want to commence with another approach and eventually evolve it into a more systematic practice.

BOARD SELF-EVALUATION IS a governance tool, and like any tool it has its advantages and disadvantages. At some organizations, the most prudent course of action might be not to engage in self-evaluation. For one thing, the process could divert board members’ attention away from a more pressing task. The board of a private company might, for instance, be better off focusing on preparing for an upcoming IPO instead of having directors — all partners from different venture-capital firms — spend precious time evaluating one another. And it should be noted that any self-evaluation conducted in a punitive spirit will more than likely fail. Nevertheless, board self-evaluation has become an increasingly mandated practice that companies need to learn how best to adopt and implement. The ultimate goal is continuous improvement. To achieve it, board self-evaluation should be an ongoing systematic process with the ultimate beneficiary being the organization as a whole.

References

1. P. Elkind, “The Fall of the House of Grasso,” Fortune, Oct. 18, 2004, 284.

2. Standard & Poor’s criteria, methodology and definitions for developing board of directors ratings are available at www2.standardandpoors.com/NASApp/cs/ContentServer?pagename=sp/sp_article/ArticleTemplate&c=sp_article&cid=1021558139012&b=10&r=1&l=EN.

3. J. Erma and J. Kivinen, “Finnish Corporate Governance,” European Lawyer (April 2004): 58.