How to Build Collaborative Advantage

Topics

For many years, multinational corporations could compete successfully by exploiting scale and scope economies or by taking advantage of imperfections in the world’s goods, labor and capital markets. But these ways of competing are no longer as profitable as they once were. In most industries, multinationals no longer compete primarily with companies whose boundaries are confined to a single nation. Rather, they go head-to-head with a handful of other giants that are comparable in size, in their access to international resources and in worldwide market position. Against such global competitors, it is hard to sustain an advantage based on traditional economies of scale and scope.

Consider the oil industry. The industry is dominated by a handful of global players such as Exxon Mobil, BP, Shell and ChevronTexaco. They each have global exploration, refining and distribution operations, leaving little room for any company to gain competitive advantage with economies of scale. Similarly, they each have brands that are more or less equally well recognized the world over, reducing opportunities for a company to seize competitive advantage with an economy of scope based on its brand power. Such relative parity among multinational corporations can also be observed in consumer electronics, information technology, pharmaceuticals, banking, professional services and even retailing.

Under these circumstances, MNCs must seek new sources of competitive advantage. While multinationals in the past realized economies of scope principally by utilizing physical assets (such as distribution systems) and exploiting a companywide brand, the new economies of scope are based on the ability of business units, subsidiaries and functional departments within the company to collaborate successfully by sharing knowledge and jointly developing new products and services.1 Multinationals that can stimulate and support collaboration will be better able to leverage their dispersed resources and capabilities in subsidiaries and divisions around the globe.

Collaboration can be an MNC’s source of competitive advantage because it does not occur automatically — far from it. Indeed, several barriers impede collaboration within complex multiunit organizations. And in order to overcome those barriers, companies will have to develop distinct organizing capabilities that cannot be easily imitated.

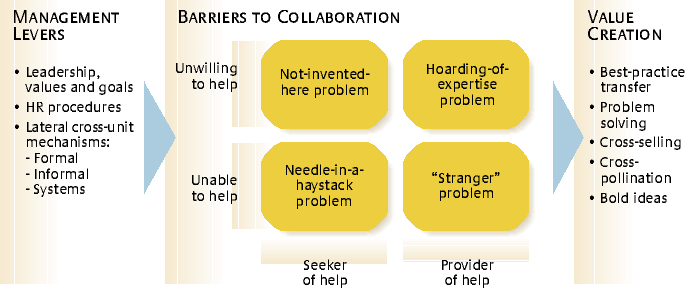

Interunit collaboration is not only difficult to achieve but also poorly understood. However, a framework that links managerial action, barriers to interunit collaboration, and value creation in MNCs can help managers “unpack” the concept. The framework conceptualizes collaboration as a set of management levers that reduce four specific barriers to collaboration, leading in turn to several types of value creation. (See “A Framework for Creating Value Through Interunit Collaboration.”) It makes most sense to explain the three elements of the framework in reverse order, beginning with value creation.

Value Creation From Interunit Collaboration

A company should not collaborate across units for collaboration’s sake alone, of course, but only if it can reap economic benefits by doing so. The potential varies by company; for instance, a firm with many related businesses or country subsidiaries stands to benefit more than a loose conglomerate of businesses. And the type of benefits will vary, too, from among five major categories:

- Cost savings through the transfer of best practices;

- Better decision making as a result of advice obtained from colleagues in other subsidiaries;

- Increased revenue through the sharing of expertise and products among subsidiaries;

- Innovation through the combination and cross-pollination of ideas; and

- Enhanced capacity for collective action that involves dispersed units.

To concretely grasp the notion of collaboration in a multinational company, consider the case of BP Plc, which has operations in more than 100 countries.2 Over the last decade, senior executives of this oil and gas giant have transformed the company from a collection of individual fiefdoms into a vast collaborative organization with significant improvements in costs, efficiency and revenues as a result.

Several major initiatives were implemented to foster collaboration between business units and country operations. Responsibility for resource allocation, for example, was taken away from individual units and handed to groups of peers —business-unit heads running similar businesses. This approach effectively forced the peers to work together to optimize the allocations for the group as a whole rather than for individual units. The company also developed “peer assist” and “peer challenge” processes, whereby managers and engineers in one unit can ask for technical and help from other units, including technical expertise and problem-solving advice. Engineers in a typical business unit spend about 5% of their time on peer assists. Peer assists are supported by several electronic knowledge-management systems as well as videoconferencing technology. And strong personal relationships also have developed as a result of the frequent rotation of managers among units and country operations.

BP also changed its promotion and reward systems. Managers undergo a 360-degree feedback process that includes reviews from peers, and managers who do not collaborate effectively throughout the organization suffer when they are being considered for promotion. In addition, 30% to 50% of bonuses for senior managers are contingent on the performance of the firm as a whole. Naturally, BP’s executives continue to change these practices as the company evolves, but the fundamental idea of creating additional value through interunit collaboration remains at the center of the company’s organizational model.

These changes have produced real, measurable results at BP. For example, there have been cost savings through the transfer of best practices: A business-unit head in the United States sought to improve the inventory turns of service stations. Tapping the expertise of her peer group, she obtained knowledge of best practices from operations in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, leading to a 20% decrease in working capital needed by U.S. service stations. Better decision making was a second result: Another unit head used a peer assist to receive input from six people in other units who had expertise in ordering oil tankers. After several meetings in which the peers advised the unit head’s team, the unit bought three tankers and took options on another three. Revenue also grew: During the development of an acetic acid plant in Western China, more than 75 people from various units flew to China to assist the core project team, enabling BP to finish the project on time and to realize revenues from the plant earlier than planned. There was cross-pollination of ideas: Managers from 15 units met to brainstorm e-commerce initiatives, and 150 new ideas were implemented. Finally, BP benefited from collective action: The company used peer groups to integrate ahead of schedule its acquisitions of Amoco Corp. and later Atlantic Richfield Co.

To obtain these important benefits, BP had to overcome barriers to collaboration between units, as all companies must do to realize similar creation of value.

Four Barriers to Interunit Collaboration

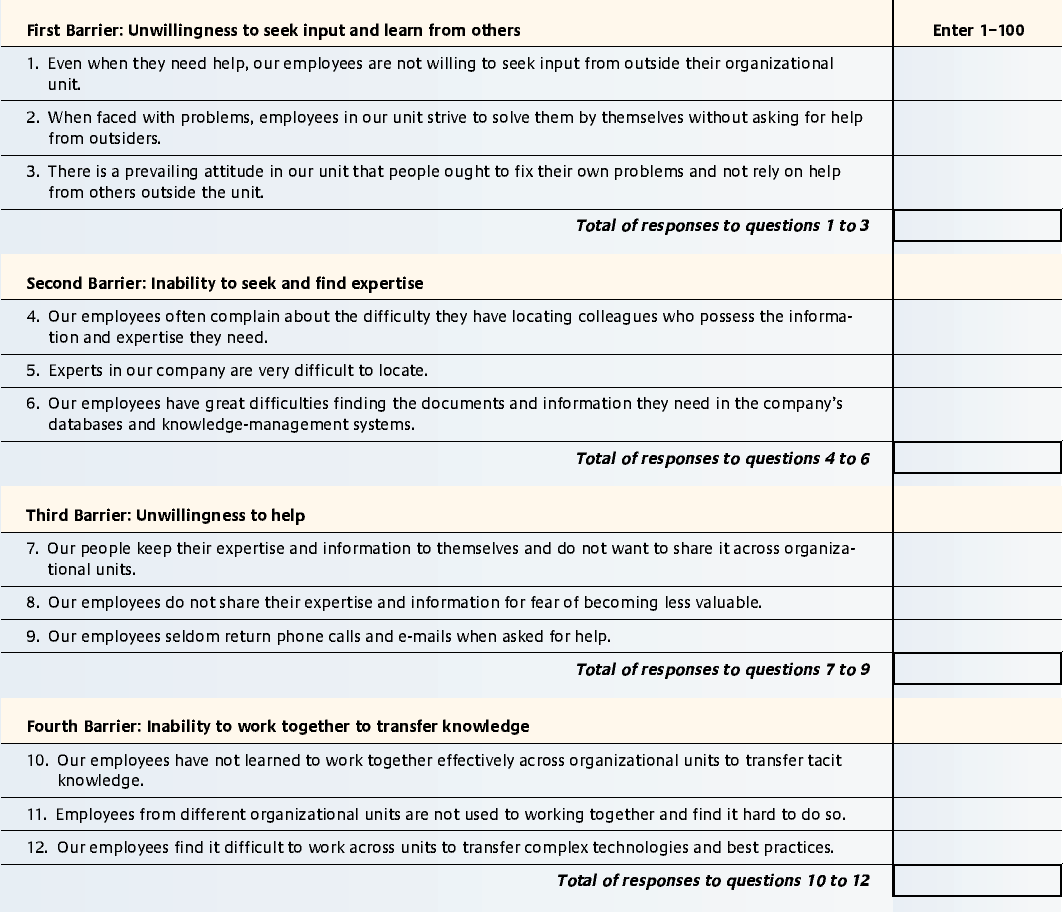

Although recent research on basic drivers of human action suggests that cooperation may be a natural human tendency, collaboration at multinationals does not just happen on its own.3 Companies often erect barriers that prevent individuals from engaging in collaborative activities that they might otherwise have undertaken. The first task, then, is to identify the barriers and their causes. The results from a survey of managers in 107 companies suggest that four barriers are prevalent in multinationals.4 (See “About the Research.”) While all four barriers to collaboration may be high in some multinationals, other companies face only one or two. It is therefore paramount to first diagnose which barriers cause a problem.

First Barrier: Unwillingness To Seek Input and Learn From Others

For several reasons, employees in one unit may close themselves off to help from those in others. Sometimes it is the norm in a unit that people are expected to fix their own problems. In other cases, formal and informal reward systems may give more credit for heroic individual efforts than for collaborative efforts. Some employees may simply believe that others have nothing to teach them. They may have developed what social psychologists call an in-group bias, in which they overvalue their own group and undervalue nonmembers.5 As in-group members spend time with one another to the exclusion of outsiders, they necessarily restrict the influx of new viewpoints and reinforce their own commonly held beliefs.6 As a result, they become prone to the not-invented-here syndrome, in which ideas, knowledge and inventions developed outside their own group are rejected.7

Consider this experience in Hewlett-Packard Co.’s European operations a few years ago. HP executives had created a new internal benchmarking system that compared the times to process computer orders at factories in various countries. Although the system revealed several underperforming country operations, the managers with worse processing times were not willing to contact and visit the best performers, partly because they did not believe that others could teach them useful practices and partly because they viewed their problems as unique (they were not). Only when senior managers intervened did the necessary collaboration between country operations take place.

Short of such after-the-fact intervention, management can use several levers to attenuate this problem. At BP, senior executives keep a close eye on the extent to which business-unit managers ask for peer assists and will intervene if someone is not seeking enough help.8 More direct help comes through peer challenges, in which peers lend on-the-scene support to help a unit improve in specific areas. Another fundamental lever is recruitment — hiring people who have a natural inclination and the confidence to ask for help. At an international chain of up-market restaurants in the United States, prospective staff members are asked, “What obstacles have you faced in a previous job that prevented you from doing a quality job, and how did you overcome those obstacles?” The company is looking for people who asked for help, communicated a problem to others and didn’t try to be a hero by fixing it alone.

Second Barrier: Inability To Seek and Find Expertise

Even when employees are willing to seek help in other business units or country subsidiaries, they may not be able to find it or to search efficiently so that the benefits outweigh the costs of searching.9 In large and dispersed MNCs, this needle-in-a-haystack problem can become a significant barrier to collaboration: Somewhere in the company someone often knows the answer to a problem, but it is nearly impossible to connect the person who has the expertise with the person who needs it.

Databases and electronic search engines can help. In most management-consulting companies, for instance, consultants upload sanitized documents containing their finished work into databases; others in the firm can then access the documents and contact the consultants who did the original work.10 Another way to help people find expertise is to create transparent benchmarking systems. Netherlands-based Ispat International N.V., one of the largest steel companies in the world, has a system that performs costing at the plant level and allows managers to compare all their operating units in the world on many dimensions. For instance, one manager found that his furnace maintenance costs were higher than those of other plants, prompting him to contact the most cost-efficient plants in this area for help.

Technology has its limits, however. Expert directories go out of date and do not fully capture what each person knows. More important, they do not allow for creative combinations of ideas and individuals. Companies may therefore need to cultivate “connectors,” that is, people who know where experts and ideas reside and who can connect people who do not know each other. Connectors tend to be long-tenured employees who have worked in many different areas in the company and hence have an extensive personal network.

A manager in GlaxoSmithKline Plc, for example, created substantial value for his company by connecting two country managers who did not know each other. A few years ago, an area director in Singapore received a phone call from the company’s managing director in the Philippines, who was looking for new product opportunities that could be introduced in his country. Acting on a hunch that there might be an opportunity in India, the area director set up a meeting with the managing director in Bombay. During his visit, the managing director from the Philippines saw that the Indian product developers were creating line extensions in the area of tuberculosis medication — not a major field in the company worldwide but one that is highly relevant in developing countries. The visit to the lab sparked a joint effort between the teams in India and Philippines, resulting in a modified TB medication and several other line extensions for the Philippine market. The area director, acting as a connector, was in effect an entrepreneur who saw an opportunity for value creation based on the combination of talent, ideas and expertise from two country subsidiaries.

Third Barrier: Unwillingness To Help

In some cases, the problem lies with the potential provider of help, not the seeker. Some employees are reluctant to share what they know — or refuse to help outright — leading to a hoarding-of-expertise problem.11 Competition between subsidiaries can undermine people’s motivation to cooperate.12 When two subsidiaries are selling products to the same markets and seeking to develop similar technologies, employees will hesitate to help people in the competing unit. Paradoxically, the emphasis on performance management over the past decade has also fueled this problem. As employees are pressured to perform, they feel that they don’t have the time to help others or they just don’t care; all that matters is delivering their own numbers. While this focus on individual performance is clearly important, executives also need to create a counterbalancing force by developing incentives aimed at fostering cooperation and a shared identity among employees.

Unwillingness to help is a significant problem in many investment banks, where bankers chase their own opportunities. When John Mack took over Morgan Stanley Group Inc. in the early 1990s, he set out to create a more collaborative culture and changed the promotion criteria.13 “Lone stars” — those who delivered great results but did not assist others — would not be promoted. To attain the coveted position of managing director, Morgan Stanley’s bankers had to demonstrate both individual performance and their contributions to others. To measure this, executives put in place a 360-degree review procedure in which peers and subordinates were asked to evaluate a person’s contributions beyond his or her department. Not surprisingly, behavior changed; cooperation within the company became much more prevalent. This system also helped break down some of the barriers to collaboration across geographic boundaries. Bankers from Europe, Asia and the United States became more willing to serve global clients collectively rather than chasing the local business of such clients in each country.

Fourth Barrier: Inability To Work Together and Transfer Knowledge

Finally, sometimes people are willing to work together but can’t easily transfer what they know to others because of the “stranger” problem. In this case, the nature of the knowledge in question requires that people already have relationships in order to understand each other. For example, when knowledge is tacit, it is difficult to explain its content and nuances to others, who in turn may find it hard to understand, thereby making the tasks of modifying and incorporating it into their own local conditions difficult, too. The same problem crops up with knowledge that is viewed as specific to a context or a culture.14 Because of these difficulties, transferring tacit or specific knowledge is likely to be more cumbersome, take longer and thus be more costly than transferring explicit or general knowledge.

These problems can be alleviated if the two parties to a transfer have developed a strong professional relationship. In that case, they are likely to have developed a shared communication frame in which each party understands how the other uses subtle phrases and explains difficult concepts. In the absence of such relations, strangers are likely to find it difficult to work together effectively. For example, in a study of time-to-market performance of new product-development projects in a global high-tech company, it was discovered that project engineers who worked with counterparts from other divisions or subsidiaries took 20% to 30% longer to complete their projects when close personal relationships between them did not exist beforehand. The engineers found it hard to articulate, understand and absorb complex technologies that were transferred between organizational units. Even though they were motivated to cooperate, they were slowed down by the need to learn to work together during the project.

To alleviate the stranger problem, executives can work to establish relationships between employees from different subsidiaries — but they must do so before specific collaborative events are launched. One of the most effective mechanisms is to rotate people through jobs at different units and subsidiaries. Employees who move to other places temporarily to work on assignments often develop strong bonds with colleagues in those locations. When people are back working in their original sites, those bonds are especially important to the success of cross-unit projects.

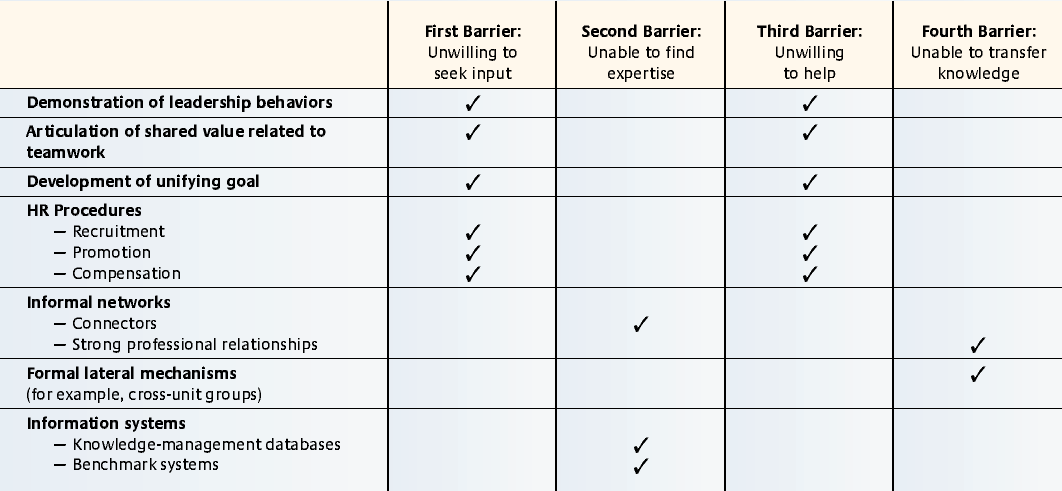

Management Levers To Promote Collaboration

Potential management levers that can reduce the barriers fall into three broad categories: leadership, values and goals; human resources procedures; and lateral cross-unit mechanisms. The latter category can in turn be divided into information systems, informal networks and formalized lateral mechanisms. Each mix of barriers in a company requires a specific mix of management levers to foster collaboration across business units, subsidiaries and departments. (See “A Road Map to Building Collaborative Advantage in Your Company.”) It’s important to carefully choose and implement a management lever or levers that will reduce a specific barrier.

Leadership, Values and Goals

These levers reduce people’s unwillingness to seek and provide help. As leaders signal the importance of collaboration by working together among themselves, articulating the shared values related to teamwork and developing unifying goals, employees are more likely to be motivated to seek and provide help.

Some companies have been particularly good at articulating powerful goals that stop myopic unit-focused behaviors and motivate people to work across company units to realize them. In 1990, Sam Walton said that Wal-Mart Stores Inc. should reach $125 billion in sales by 2000, up from $32 billion at the time. Nike Inc. wanted to “Crush Adidas,” its main rival in the athletic shoes industry in the 1960s. Over the past few years employees at Airbus S.A.S. have informally aspired to beating Boeing Co. In the late 1990s, Starbucks Corp. articulated the very ambitious goal of establishing itself as “the most recognized and respected brand in the world.”15 Such goals both stretch and unify an organization’s employees; they cannot be reached unless everyone stops pursuing self-promoting, narrow-minded goals and becomes motivated to pull together by seeking and providing help across units.

Levers involving leadership, values and goals, however, do not affect the people’s ability to find help and work together. A leader who preaches collaboration may motivate the troops but cannot by words alone help them locate experts or enable employees to work well together. Leadership behaviors and the articulation of shared values and goals are necessary but not sufficient conditions for effective collaboration in MNCs.

Human Resources Procedures

Recruitment and promotion criteria also reduce unwillingness to seek or provide help. By selecting job candidates who have an inclination to search for and offer help, an organization will over time be populated with people who thrive on cooperative work. Likewise, making demonstrated collaborative behaviors a criterion for promotion to senior positions in a company ensures that the top team will, over time, be composed of leaders who exhibit collaborative behaviors. In addition, having such a promotion criterion sends a powerful signal to employees vying for leadership positions; those who do not have the inclination to collaborate are likely to leave a company that enforces the rule consistently. Finally, compensating employees based on their collaborative behaviors is also a useful lever.

To make the promotion and compensation levers work, a company needs to change its annual performance criteria. Intuit Inc., the financial-software company, has implemented an annual performance system in which employees are evaluated on two questions: “What was accomplished?” and “How were the goals accomplished?”16 The “how” part evaluates an employee’s collaborative efforts across functions and business units in reaching those goals. An employee who did not collaborate enough will receive a lower mark for the year, even if he reached the individual goals.

Lateral Cross-Unit Mechanisms

If the problem is the inability to find help, then the most effective levers tend to be these three: the cultivation of connectors; the development of electronic yellow pages that list experts by area; and the development of benchmark systems that allow employees to identify best practices in the company. If the problem is the inability to work together to transfer knowledge, an effective lever is the cultivation of strong professional relationships between employees from different units and the development of formal cross-unit groups and committees that structure regularly occurring interactions. These provide a forum for people to get to know one another and develop personal bonds that facilitate sharing.

While all four barriers to collaboration may be high in some MNCs, other companies face only one or two. It is therefore paramount to first diagnose which barriers cause a problem. For example, if the problem is an inability to find help, putting in a knowledge-management or benchmarking system would be appropriate, but changing HR procedures would not — if people cannot find experts, it makes no sense to make promotion contingent on doing so. In contrast, if the problem is a widespread not-invented-here syndrome, changing the HR procedures should help, but a new knowledge-management system is unlikely to have any effect on employees who will not seek help or who hoard what they know.

Potential Downsides of Collaboration

While collaboration can create substantial value, it also has a downside that executives need to manage. One pitfall is that it can easily be overdone. Prompted by collaboration initiatives, employees may begin to participate in all kinds of meetings in which nothing of substance is accomplished. Such unproductive collaboration will undermine overall company performance. For example, when executives were just beginning to develop collaborative behaviors within BP, employees started to form an unforeseen number of cross-unit networks. An audit within the oil exploration business alone identified several hundred of these networks, including one on helicopter utilization. According to John Leggate, who ran several business units during that time, “People always had a good reason to meet, but increasingly we found that people were flying around the world and simply sharing ideas without always having a strong focus on the bottom line.” BP’s executives had to reduce the number of networks and limit interunit meetings to those focused on getting specific results.

Management levers to create a collaborative organization must be counterbalanced with performance management of each individual and business unit, including a clear specification of who’s responsible for what. At BP, each manager has an individual performance contract that is coupled with clear expectations for participating across the organization. These managers have a “T-shaped” role — while their primary responsibility is to deliver results for their own business unit or country subsidiary (the vertical part of the T), their other responsibility is to seek help and to aid others (the horizontal part of the T). This dual role is difficult to carry out well and is a source of stress. Effective T-shaped managers tend to be good at prioritizing and delegating to subordinates. While those are attributes of any good manager, they are especially important in MNCs that require their managers to be effective along both dimensions of the T.

The Central Role of Collaboration

How one views the importance of collaboration relates directly to ideas about the purpose of any corporation and the reason for its existence. In the standard economic argument, firms arise when markets fail.17 In consonance with that view, market failures in the exchange of goods, people and knowledge across geographic boundaries have long occupied center stage in economic theories of the multinational enterprise.18 When global markets were relatively underdeveloped and prone to failure, this view made a legitimate contribution to our understanding. But now that global markets have become much more developed and relatively more efficient, it is time to consider an equally long-standing conception of why firms exist.19

In the alternative view, firms come into being in order to enable human beings to achieve collaboratively what they could not achieve alone. If one accepts this as the true purpose of any organization, then the main focus of executives’ attention should be on how to foster collaboration within their companies. Especially in an era when advantages based on traditional economies of scale and scope are rapidly diminishing, the successful exploitation of collaborative possibilities may hold the key for multinationals seeking to gain or maintain leads over their rivals.

References

1. See B. Kogut and U. Zander, “Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology,” Organization Science 3, no. 3 (1992): 383–397; C. Hill, “Diversification and Economic Performance: Bringing Structure and Corporate Management Back Into the Picture,” in “Fundamental Issues in Strategy,” eds. R. Rumelt, D. Schendel and D. Teece (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1995), 297–322; and J. Nahapiet and S. Ghoshal, “Social Capital, Intellectual Capital and the Organizational Advantage,” Academy of Management Review 23, no. 2 (April 1998): 242–266.

2. For an in-depth look at BP on this issue, see S.E. Prokesch, “Unleashing the Power of Learning: An Interview With British Petroleum’s John Browne,” Harvard Business Review 75, no. 5 (September–October 1997): 146–168; and M.T. Hansen and B. Von Oetinger, “Introducing T-Shaped Managers: Knowledge Management’s Next Generation,” Harvard Business Review 79, no. 3 (March 2001): 106–116. The section on BP in the text draws on the latter article.

3. See P.R. Lawrence and N. Nohria, “Driven: How Human Nature Shapes Our Choices” (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002).

4. This section draws on M. Hansen, “Turning the Lone Star Into a Real Team Player,” Financial Times, Aug. 7, 2002, 11–13.

5. See, for example, M.B. Brewer, “Ingroup Bias in the Minimal Intergroup Situation: A Cognitive Motivational Analysis,” Psychological Bulletin 86 (1979): 307–324; and H. Tajfel and J.C. Turner, “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior,” in “Psychology of Intergroup Relations,” 2nd ed., eds. S. Worchel and W.G. Austin (Chicago: Nelson Hall Publishers, 1986), 7–24.

6. See P.J. Oakes, S.A. Haslam, B. Morrison and D. Grace, “Becoming an In-Group: Reexamining the Impact of Familiarity on Perceptions of Group Homogeneity,” Social Psychology Quarterly 58, no. 1 (March 1995): 52–60; and D.A. Wilder, “Reduction of Intergroup Discrimination Through Individuation of the Out-Group,” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 36 (1978): 1361–1374.

7. See R.H. Hayes and K.B. Clark, “Exploring the Sources of Productivity Differences at the Factory Level” (New York: Wiley, 1985); and R. Katz and T.J. Allen, “Investigating the Not Invented Here (NIH) Syndrome: A Look at the Performance, Tenure and Communication Patterns of 50 R&D Project Groups,” in “Readings in the Management of Innovation,” 2nd ed., M.L. Tushman and W.L. Moore, eds. (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1988), 293–309.

8. See also S. Ghoshal and L. Gratton, “Integrating the Enterprise,” MIT Sloan Management Review 44, no. 1 (fall 2002): 31–38.

9. See M.T. Hansen, “The Search-Transfer Problem: The Role of Weak Ties in Sharing Knowledge Across Organization Subunits,” Administrative Science Quarterly 44, no. 1 (March 1999): 82–111; and M.T. Hansen and B. Lovas, “How Do Multinational Companies Leverage Technological Competencies? Moving From Single to Interdependent Explanations,” Strategic Management Journal, in press.

10. For more details on knowledge management in management-consulting companies, see M.T. Hansen, N. Nohria and T. Tierney, “What’s Your Strategy for Managing Knowledge?” Harvard Business Review 77, no. 2 (March–April, 1999): 106–116.

11. See A.K. Gupta and V. Govindarajan, “Knowledge Flows Within Multinational Corporations,” Strategic Management Journal 21 (April 2000): 473–496.

12. See W. Tsai, “Social Structure of ‘Coopetition’ Within a Multiunit Organization: Coordination, Competition and Intraorganizational Knowledge Sharing,” Organization Science 13, no. 2 (March–April 2002): 179–190.

13. For a detailed description of these changes at Morgan Stanley, see M.D. Burton, T.J. DeLong and K. Lawrence, “Morgan Stanley: Becoming a ‘One-Firm’ Firm,” Harvard Business School case no. 9-400-043 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 1999); and M.D. Burton, “The Firmwide 360-Degree Performance Evaluation Process at Morgan Stanley,” Harvard Business School case no. 9-498-053 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 1998).

14. See M. Haas, “Acting on What Others Know: Distributed Knowledge and Team Performance” (unpublished Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2002).

15. For an in-depth look at inspiring common goals, see J. Collins and J. Porras, “Building Your Company’s Vision,” Harvard Business Review 74, no. 5 (September–October 1996): 65–77.

16. See M.T. Hansen and C. Darwall, 2003, “Intuit Inc.: Transforming an Entrepreneurial Company Into a Collaborative Organization,” Harvard Business School case 9-403-064 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2003).

17. See R.H. Coase, “The Nature of the Firm,” Econometrica 4 (1937): 386–405.

18. See R.E. Caves, “Multinational Enterprise and Economic Analysis (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

19. See C. Barnard, “The Functions of the Executive” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1939).