How Outlawing Collegiate Affirmative Action Will Impact Corporate America

Leaders who remain committed to hiring high-potential talent and offering equal opportunities to members of disadvantaged groups must reconsider their workforce pipelines.

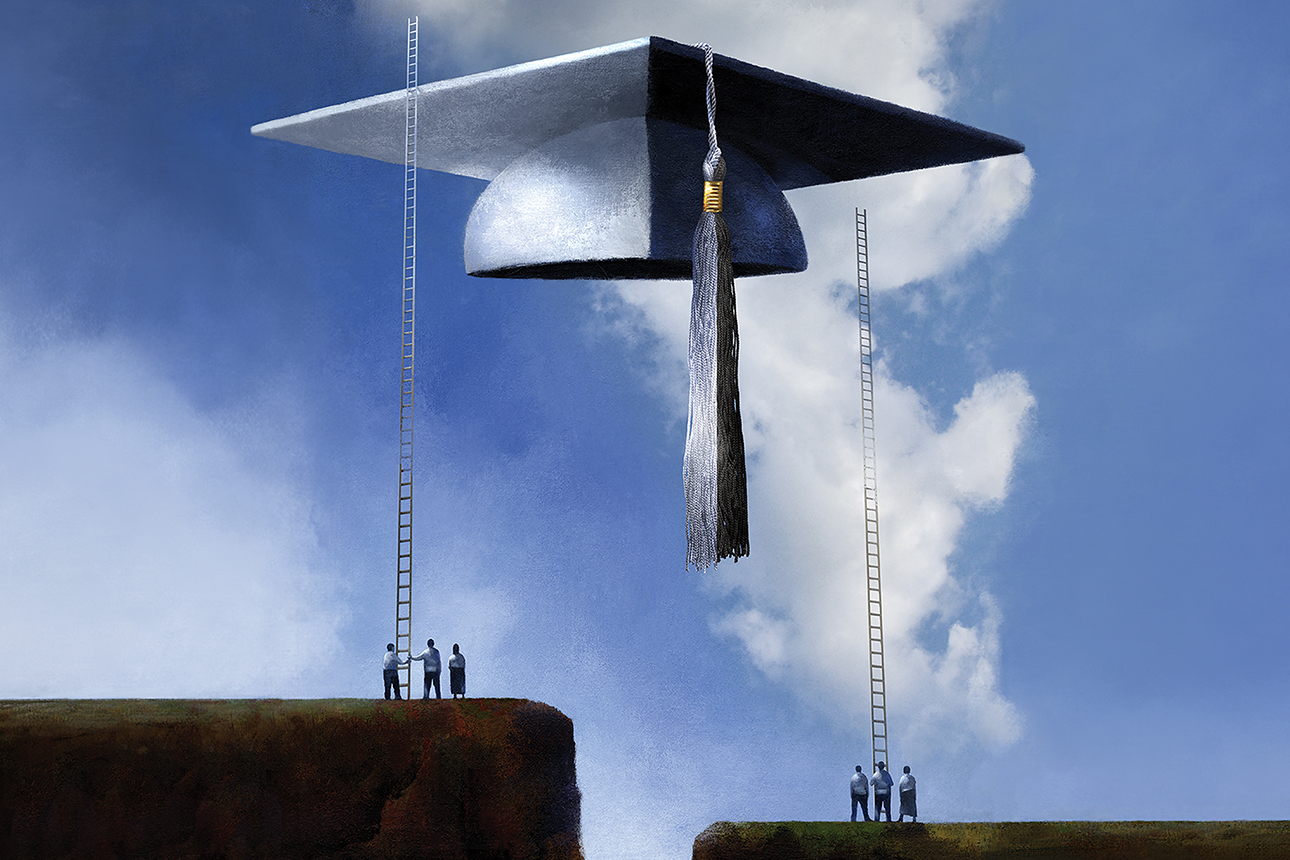

Michael Glenwood Gibbs/theispot.com

On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled 6-3 in favor of outlawing the use of race and ethnicity as factors in college admissions. This was a momentous decision that stands to have widespread societal and organizational implications. Although the scope of the ruling was limited to college admissions, we can draw upon existing data to forecast the impact on corporate America. The evidence clearly points to two key outcomes: First, collegiate patterns of racioethnic diversity will change fairly dramatically; and second, these changes will have considerable downstream consequences for workplace composition as well as patterns of racioethnic inequity across a host of other measures.

As tempting as it might be to view those conclusions as hyperbolic, research on three decades of state-level affirmative action bans strongly suggests otherwise. In fact, eradicating affirmative action has led to reductions in the proportions of underrepresented (Black and Hispanic) students in undergraduate and graduate programs, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and math; it has also led to fewer underrepresented students enrolled in and graduating from medical and law schools.1 These effects tend to be lasting — and, importantly, implementing alternative policies that don’t explicitly consider race and ethnicity has done little to counter them.2

Email Updates on the Future of Work

Monthly research-based updates on what the future of work means for your workplace, teams, and culture.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Extending these state-level findings to the national level suggests that employers will have less racioethnically diverse college-educated talent to draw upon when filling their vacancies, particularly from premier institutions. Alternatively, the Black and Hispanic candidates within their applicant pools are less likely to be selected because they will be less credentialed as a result of having fewer degrees or having graduated from lower-ranked colleges, where they are more likely to apply and be accepted post-affirmative action. A somewhat less-intuitive consequence is that the White (and Asian) graduates of more prestigious colleges and universities will have had less exposure to people of other racioethnic backgrounds. This has implications for their multicultural competence — the ability to relate to those dissimilar from oneself — and may help account for why employers tend to pay higher starting salaries to graduates of more racioethnically diverse business schools and universities.3

The fallout within Black and Hispanic communities stands to be devastating. Most notably, there will be fewer minority professionals to help meet the needs of racioethnically similar minority clientele.

References

1. P. Hinrichs, “The Effects of Affirmative Action Bans on College Enrollment, Educational Attainment, and the Demographic Composition of Universities,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 94, no. 3 (August 2012): 712-722; L.M. Garces, “Understanding the Impact of Affirmative Action Bans in Different Graduate Fields of Study,” American Educational Research Journal 50, no. 2 (April 2013): 251-284; L.M. Garces and D. Mickey-Pabello, “Racial Diversity in the Medical Profession: The Impact of Affirmative Action Bans on Underrepresented Student of Color Matriculation in Medical Schools,” The Journal of Higher Education 86, no. 2 (March-April 2015): 264-294; D.P. Ly, U.R. Essien, A.R. Olenski, et al., “Affirmative Action Bans and Enrollment of Students From Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Groups in U.S. Public Medical Schools,” Annals of Internal Medicine 175, no. 6 (June 2022): 873-878; J.M. Scott, P. Wilson, and A. Pals, “‘Freedom Is Not Enough...’: Affirmative Action and J.D. Completion Among Underrepresented People of Color,” AccessLex Institute research paper no. 23-05, SSRN, April 20, 2023, https://papers.ssrn.com; D. Yagan, “Supply vs. Demand Under an Affirmative Action Ban: Estimates From UC Law Schools,” Journal of Public Economics 137 (May 2016): 38-50; and R.R.W. Brooks, K. Rozema, and S. Sanga, “Affirmative Action and Racial Diversity in U.S. Law Schools, 1980-2021,” SSRN, July 10, 2023, https://papers.ssrn.com.

2. Z. Bleemer, “Affirmative Action and Its Race-Neutral Alternatives,” Journal of Public Economics 220 (April 2023): 1-16; M.C. Long and N.A. Bateman, “Long-Run Changes in Underrepresentation After Affirmative Action Bans in Public Universities,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 42, no. 2 (June 2020): 188-207; and L. Perez-Felkner, “Affirmative Action Challenges Keep On Keeping On: Responding to Shifting Federal and State Policy,” Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 25, no. 1 (2021): 19-23.

3. D.R. Avery and K.M. Thomas, “Blending Content and Contact: The Roles of Diversity Curriculum and Campus Heterogeneity in Fostering Diversity Management Competency,” Academy of Management Learning & Education 3, no. 4 (December 2004): 380-396; D. Lynch, “Does Diversity Matter?: Evidence From the Relationship Between an Institution’s Diversity and the Salaries of Its Graduates” (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 2013); and J.D. Fink and K.E. Fink, “Diversity and the Starting Salaries of Undergraduate Business School Students,” Journal of Education for Business 94, no. 5 (2019): 290-296.

4. E.N. Chapman, A. Kaatz, and M. Carnes, “Physicians and Implicit Bias: How Doctors May Unwittingly Perpetuate Health Care Disparities,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 28, no. 11 (November 2013): 1504-1510.

5. L. Zhang, “Regulatory Spillover and Workplace Racial Inequality,” Administrative Science Quarterly 67, no. 3 (September 2022): 595-629.

6. A.S. Venkataramani, E. Cook, R.L. O’Brien, et al., “College Affirmative Action Bans and Smoking and Alcohol Use Among Underrepresented Minority Adolescents in the United States: A Difference-in-Differences Study,” PLoS Medicine 16, no. 6 (June 18, 2019): 1-16.

7. S.M. Gaddis, “Discrimination in the Credential Society: An Audit Study of Race and College Selectivity in the Labor Market,” Social Forces 93, no. 4 (June 2015): 1451-1479.

8. B. Erdogan and T.N. Bauer, “Overqualification at Work: A Review and Synthesis of the Literature,” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 8 (2021): 259-283.

9. R.E. Ployhart and B.C. Holtz, “The Diversity-Validity Dilemma: Strategies for Reducing Racioethnic and Sex Subgroup Differences and Adverse Impact in Selection,” Personnel Psychology 61, no. 1 (spring 2008): 153-172.